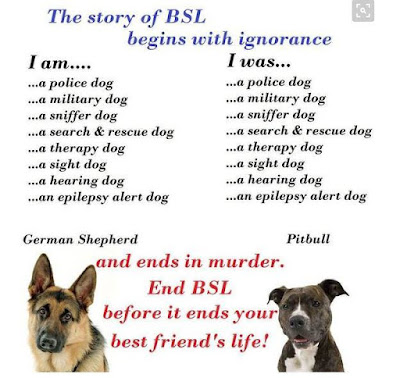

Veterinarians, their clients, and their clients’ pets in 300 cities and towns in the United States live with special burdens and added costs because of ordinances banning or restricting dogs of one or more breeds and breed mixes. Thirty-six breeds of dogs and mixes of those breeds have been restricted, in various combinations and groupings.

These restrictions and bans compromise the human-animal bond and complicate the professional landscape for veterinarians.

AVMA, the CDC, the National Animal Control Association, the Association of Pet Dog Trainers, and virtually all animal welfare charities oppose breed-specific regulation.

1 AVMA recently released a statement opposing breed discrimination by insurers. There has never been any evidence that breed bans or restrictions contribute to improved public safety. The Netherlands repealed its breed ban last year because, based upon a report from a committee of experts, the ban had not led to any decrease in dog bites.

2 Italy repealed its breed-specific regulations.

3. DEMONIZED DOGS THEN

As America’s conflict over slavery intensified, public attitudes towards the bloodhound paralleled the increasingly negative attitudes towards the dogs’ most publicized function: slave catching. The depiction of the slave catcher’s dog in stage re-enactments of UNCLE TOM’S CABIN made him an object of dread to ordinary citizens, and an object of attraction to dog owners who wanted dogs for anti-social purposes. As these owners acquired more and more

dogs, serious incidents – and fatalities – associated with dogs identified as bloodhounds became prominent in the public press.

4 In the 20th century, other groups of dogs replaced the bloodhound as objects of dread, most notably the German Shepherd (which, in 1925, a New York City magistrate said should be banned ;5 and which were, in fact, banned in Australia from 1928 until 19736), the Doberman Pinscher (frequently associated with soldiers of the Third Reich), and the Rottweiler (portrayed as the guardian of Satan’s child in the popular 1976 film THE OMEN).

DEMONIZED DOGS NOW

Early in the 20th century, pit bull type dogs enjoyed an excellent popular reputation. An American Bull Terrier had symbolized the United States on a World War One propaganda poster. “Tighe”, a pit bull type dog, had helped sell Buster Brown shoes. Pete the Pup, the “little rascals” pit bull pal of the Our Gang comedies, was the first AKC-registered Staffordshire Terrier (Registration number A-103929).

In 1976, the Federal government amended the Animal Welfare Act to make trafficking in dogs for the purposes of dog fighting a crime. The media focused on the dogs, rather than on the people who fought the dogs; and the dogs made headlines. Monster myths of super-canine powers began to dominate the stories.7 As had happened to the bloodhound, the myths attracted the kind of owners who use dogs for negative functions. Sensationalized, saturation

news reporting of incidents involving dogs called pit bulls, linked them in the public mind almost exclusively with criminal activity.

This small subset of dogs being used for these negative purposes came to define the millions of pit bull type dogs living companionably at home.

WRONG NUMBERS, NOT STATISTICS

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) attempted to identify the breeds of dogs involved in fatal human attacks. 8 The study period, 1979 – 1998, happened to coincide with the sensationalized media portrayal and resulting notoriety of pit bulls and Rottweilers.4,7 In reporting their findings, the researchers made clear that the breeds of dogs said to be involved in human fatalities had varied over time, pointing out that the period 1975-1980 showed a different distribution of breeds than the later years.8 Subsequently, Karen Delise of the National Canine Research Council reported that, in the decade 1966-1975, fewer than 2% of all dogs involved in fatal attacks in the United States were identified as of the breeds that figured prominently in the CDC study. 4

The CDC has since concluded that their single-vector epidemiological approach did not “identify specific breeds that are most likely to bite or kill, and thus is not appropriate for policy making decisions related to the topic.”1 AVMA has published a statement to the same effect.9 “Dog bite statistics are not statistics, and do not give an accurate representation of dogs that bite.”10 Nevertheless, the questionable data-set covering only one particular 20-year period, and not the researchers’ conclusions and recommendations, is repeatedly cited in legislative forums, in the press, and in the courts to justify breed discrimination.

Dr. Gail Golab of the AVMA, one of the researchers involved in the CDC project, said, “The whole point of our summary was to explain why you can't do that. But the media and the people who want to support their case just don't look at that.”11 The researchers had suspected that media coverage of “newsworthy” breeds could have resulted in “differential ascertainment” of fatalities by breed attribution. Relying on media archives, of the 327 fatalities identified within the 20-year period, the researchers located breed or breed-mix identifications for 238, approximately 72% of the total.

More than 25 breeds of dogs were identified.8 Of those incidents for which the researchers could find no breed attributions (n = 89), Karen Delise of the National Canine Research Council later located breed attributions in 40; and 37 of these cases involved dogs identified as other than Rottweiler and pit bull, a result that confirmed the researchers concerns regarding ”differential ascertainment” of incidents because of breed bias .

12. In addition to the problem of the small, unrepresentative, and incomplete data sets, the researchers expressed concern about the reliability of the breed identifications they had obtained, and were uncertain how to count attacks involving “cross bred” dogs.8 It is estimated that at least one-half of the dogs in the United States are mixed breed dogs.13 What is the reliability or significance of a visual breed identification of a dog of unknown history

and genetics?

Pit bull is not a breed, but describes a group of dogs that includes American Staffordshire Terriers, Staffordshire Bull Terriers, American Pit Bull Terriers, an increasing number of other pure breeds, and an ever-increasing group of dogs that are presumed, on the basis of appearance, to be mixes of one or more of those breeds. Ordinances restricting or banning dogs generally rely on someone’s visual assessment of their physical characteristics.

The modern science of genetics renders a breed label based on visual identification problematic. According to Sue DeNise, vice-president of MMI Genomics, creators the Canine Heritage Breed Test for mixed breed dogs, each test result is furnished to the dog owner with the following proviso: “Your dog’s visual appearance may vary from the listed breed(s) due to the inherent randomness of phenotypic expression in every individual.”

14 Scott and Fuller, in their landmark genetic studies, produced offspring of considerable phenotypic variety from purebred and F1 crosses.

Breed identification of a mixed breed dog based on its phenotype is unscientific, and is likely to be contradicted by a DNA test. A study to be published in the Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science points to a substantial discrepancy between visual identifications of dogs by adoption agency personnel and the breeds identified in the same dogs through DNA analysis.

Of 16 mixed breed dogs labeled as being partly a specified breed, in only 25% of these dogs was that breed also detected by DNA analysis. 15

THE LANDSCAPE OF BREED SPECIFIC LEGISLATION

Legislative restrictions range from an outright ban in Denver, Colorado, where, since 1989, thousands of dogs have been seized and killed16; to a regulatory catalog of muzzling, neutering, and confinement mandates that only apply to the regulated group, however defined; and to requirements that owners pay special license fees and maintain higher levels of liability insurance. Apart from statutory requirements, some homeowners’ insurers are imposing special requirements before they will include liability coverage for dogs of certain breeds, or are declining to cover dogs of an increasing number of breeds altogether.

Rental apartments, planned communities, campgrounds, and neighborhood associations impose a wide range of special rules or restrictions regarding many breeds of dogs. In a jurisdiction with breed-specific regulations, veterinarians can easily be drawn into an official controversy. When a police officer in Maquoketa, Iowa identified a dog as a pit bull and served notice on the owner that she had to remove it from the town, the owner appealed to the state Office of Citizen’s Aide/Ombudsman.

The 21- page report that resulted, chronicles the failure to arrive at an agreed-upon breed identification for the dog. Among other documents, the owner produced vaccination certificates from her veterinarian that described

the dog as a “Rott-mix.” The town countered with another veterinarian’s intake form that described the dog as a “pit mix”.17

In January, 2009, the U.S. Department of the Army banned Chows, Rottweilers, pit bulls, wolfhybrids and Doberman Pinschers from all privatized military housing. The previous July, Fort Hood, Texas banned pit bulls and pit bull mixes from government housing. The Fort Hood mission support order specifies that, in the event of a dispute, “the Fort Hood Veterinary Clinic [emphasis mine] will be the deciding authority to determine if a dog is a Pit Bull [sic] cross.”18

HUMANE COMMUNITIES ARE SAFER COMMUNITIES

In “A Community Approach to Dog bite Prevention,” the AVMA Task Force reported, “An often asked question is what breed or breeds of dogs are ‘most dangerous’? This inquiry can be prompted by a serious attack by a specific dog, or it may be the result of media-driven portrayals of a specific breed as ‘dangerous.’ . . . singling out 1 or 2 breeds for control . . . ignores the true scope of the problem and will not result in a responsible approach to protecting a community’s citizens.”

10 Delise, based upon her study of fatal attacks over the past five decades, has identified poor ownership/management practices involved in the overwhelming majority of these incidents: owners obtaining dogs, and maintaining them as resident dogs outside of the household for purposes other than as family pets (i.e. guarding/protection, fighting, intimidation/status); owners failing to humanely contain, control and maintain their dogs (chained dogs, loose roaming dogs, cases of abuse/neglect); owners failing to knowledgeably supervise interaction between children and dogs; and owners failing to spay or neuter resident dogs not used for competition, show, or in a responsible breeding program.4

Focusing on breed or phenotype diverts attention from strategies veterinarians and other animal experts have consistently identified as contributing to humane and safer communities

BREED LABELING AND VETERINARY PRACTICE

In an environment of breed discrimination, the breed identification of a dog can have serious consequences with municipal authorities, animal shelters, landlords, and insurers, all of which will compromise the bond between a family and their dogs. Ordinances may obligate owners with expensive special housing and containment requirements. Owners may even be forced to

choose between sending a beloved family pet away, or surrendering it to be killed.

Veterinarians who attempt to visually identify the breeds that might make up a dog do not derive any benefit from this activity, while the client may hold the veterinarians to the same professional standard as they would with respect to the delivery of medical services.

It is impossible to breed label dogs of unknown origin and genetics solely on the basis of their appearance. There is so much behavioral variability within each breed, and even more within breed mixes, that we cannot reliably predict a dog’s behavior or suitability based on breed alone. Each dog is an individual. 19 Owners may be influenced as to what behavior to expect from their dog, based upon breed stereotypes.20 Veterinarians must take the lead, and free themselves from stereotypes, in order to better serve their clients, their clients’ animals, and society.

Source & References

By...... Jane Berkey

More to come.....

The first symptom of dog being anti social is excessive barking on seeing strangers. The guide on managing anti-social dog helped a lot.

ReplyDelete